researchaudio.io • AI research & system design

Learning to reason in 13 parameters

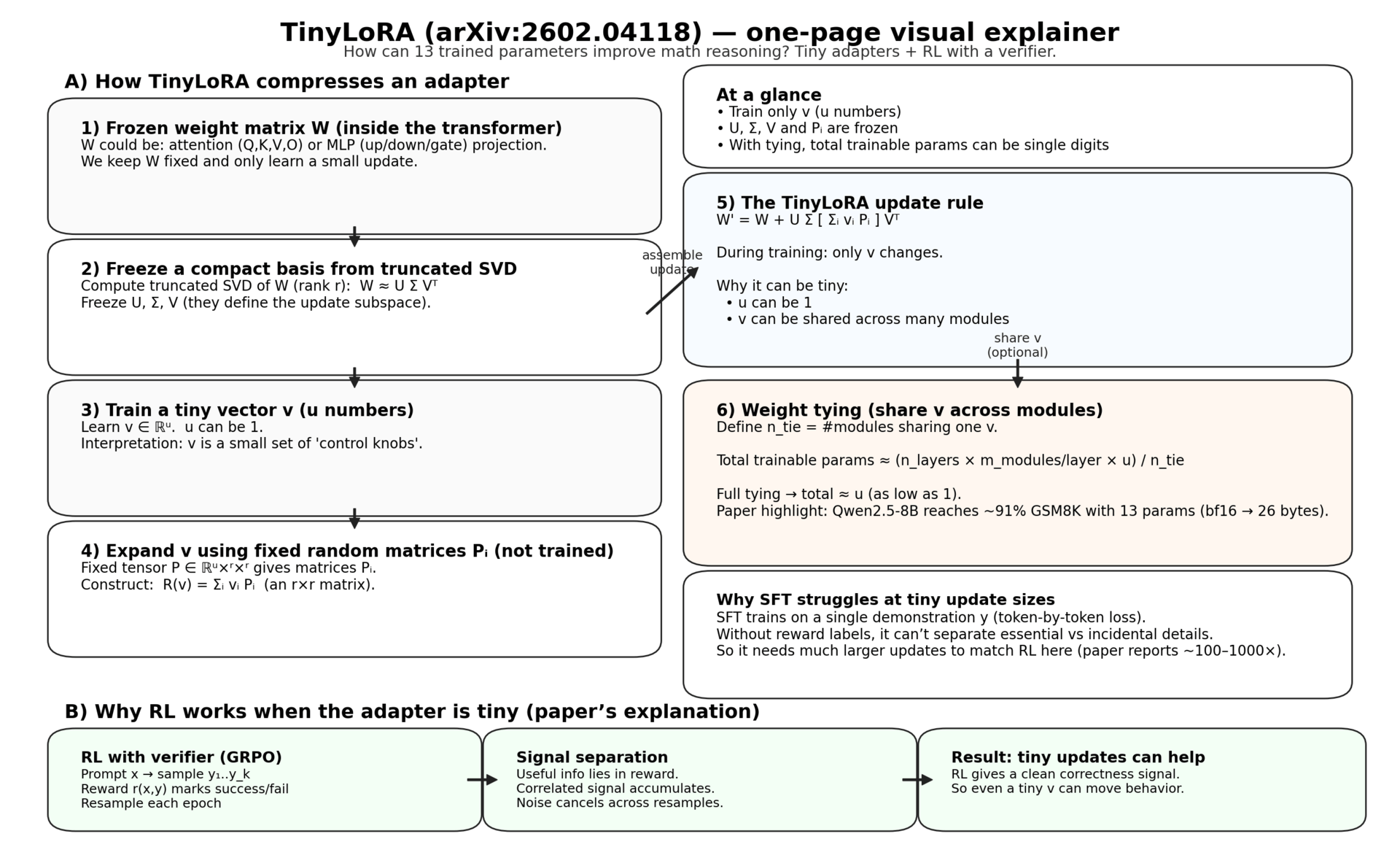

TinyLoRA is an extreme adapter: instead of updating millions of weights, it updates a handful of numbers—and reinforcement learning with verifiable rewards makes those tiny updates surprisingly effective.

|

In one sentence The paper argues that when your finetuning objective is RL with a verifier, the “useful signal” you need to store can be so compact that a model can change behavior meaningfully with an adapter that is literally tens of bytes. |

What happened here?

We’ve gotten used to a weird modern fact: a big model can be “post-trained for reasoning” and suddenly it writes longer scratchwork, checks itself, and solves math problems it used to miss. The usual story is that this requires significant training: either full finetuning, or at least millions of adapter parameters.

This paper tries to poke that story with a very sharp stick. What if the base model already contains most of the capability, and the post-training step is mostly steering—changing the mode the model is in—rather than injecting lots of new knowledge? If that’s true, then the “control channel” you need might be tiny.

The authors propose an adapter family called TinyLoRA that shrinks the trainable degrees of freedom far below what standard LoRA can reach. Their headline datapoint: with the right setup, you can train an 8B-class model to strong GSM8K accuracy while updating only 13 parameters. That’s 26 bytes in bf16.

If you build or study reasoning systems, you should care for two reasons. First, it changes the economics of adaptation: storing a “skill” might cost kilobytes, not megabytes. Second, it pushes on a deeper question: what does RL for reasoning actually learn when the update is so small?

The core result, in numbers

The paper trains Qwen2.5 instruction models on math reasoning tasks using either supervised finetuning (SFT) or reinforcement learning (specifically GRPO) with an exact-match verifier. On GSM8K, they show a smooth curve: as you increase the adapter size from 1 parameter to thousands to millions, performance improves, and TinyLoRA sits at the extreme low end.

The striking part is not that tiny adapters do something. It’s that, under RL, they do a lot. The paper reports that a model trained with GRPO reaches about 91% GSM8K accuracy with 13 parameters, and that under 100 parameters it can already cross 90% accuracy.

Meanwhile, the same tiny-adapter regime looks very different under SFT. The paper’s sweep shows SFT performing much worse at 13 and 120 parameters, and it argues that SFT needs 100–1000× larger updates to match RL’s performance in this regime. That gap is the main plot twist: not “TinyLoRA exists,” but “RL makes the tiny update channel usable.”

Diagram 1: What “tiny update” means

Adapter size is usually measured in trainable parameters. LoRA @ rank 1 on an 8B model: still millions of parameters (because it scales with width) TinyLoRA: can be tens of parameters total even single digits (13 parameters is 26 bytes in bf16) Interpretation: you're not "rewriting the model" you're turning a small set of knobs

TinyLoRA, explained like an engineer

Let’s start with the usual LoRA story. You have a frozen weight matrix W inside a transformer (say the query projection). LoRA adds a low-rank update ΔW that factorizes as A·B. You train A and B, and you keep W fixed. The appeal is that A and B are smaller than W, so you train fewer parameters and your update is modular.

The problem: even “small” LoRA is still tied to the model’s width. At rank 1, A is shaped like (d×1) and B like (1×k), so the parameter count is still O(d+k). In big models, that’s still a lot per layer, and across all layers it’s millions.

A more recent variant, LoRA-XS, compresses further by expressing the update in the singular-vector basis of W. It uses a truncated SVD of W (U, Σ, V) and learns a small matrix R that recombines those dominant directions. This changes the scaling from O(d·r) per module to O(r²) per module. Better, but you still need at least one parameter per adapted module.

TinyLoRA’s trick is to make R itself “generated” from something even smaller: a trainable vector v of dimension u, pushed through a fixed random projection tensor. Instead of learning an entire r×r matrix, you learn u numbers, and those numbers get mapped into r×r space via a bank of fixed random matrices.

LoRA: W' = W + A B LoRA-XS: W' = W + U Σ R Vᵀ (U, Σ, V frozen from SVD(W); only R trainable) TinyLoRA: R(v) = Σ_i v_i P_i (P_i fixed random r×r matrices) W' = W + U Σ R(v) Vᵀ Train only v ∈ ℝ^u

You can pick u=1. Then each module has just one trainable scalar controlling its update in the SVD basis. But the paper goes further: weight tying. Instead of giving every module its own scalar (or tiny vector), you share the same v across many modules (or even across the entire network). The paper defines a tying factor, essentially “how many modules share one v,” which lets the total number of trained parameters drop to u for the whole model.

There are tradeoffs. Sharing v across many modules reduces capacity, but it also makes the update extremely compact and cheap to store, transmit, or swap at inference time. The paper explores several sharing patterns, including “structured” sharing (tie similar module types) and “tiled” sharing (tie by depth neighborhood), and finds that tiling can outperform structured tying in the bit-constrained regime.

Why reinforcement learning makes tiny updates work

Here’s the part of the paper I expect to age the best: the argument for why RL is more “information-dense” than SFT when your adapter is tiny.

In SFT, the training target is a demonstration y. The model is trained token-by-token to imitate y given x and the previous tokens. That’s a dense signal in the sense that you get a loss on every token. But it’s also a messy signal: the model is not told which parts of y are essential for correctness and which parts are incidental.

In RL with a verifier, you sample multiple candidate solutions and you get a reward r(x, y). If r is binary, that reward is at most 1 bit of information per sample (success/fail). That sounds tiny. But crucially, it’s the right bit: it labels success directly. The paper argues that most of the raw continuation tokens are effectively noise unless you know which continuations were rewarded.

Then comes the key move: resampling across epochs. Because RL re-generates samples using the updated policy, reward-correlated features accumulate, while uncorrelated variation cancels out. This creates a form of “signal separation”: the learning rule can, over time, latch onto whatever feature differences predict reward, without needing to encode all the irrelevant detail.

Diagram 2: Signal separation in one picture

You can think of each sample as having features:

y = {task-relevant features} + {style quirks} + {random detours}

SFT sees: (x, y) with no annotation

→ must treat everything as potentially important

RL sees: (x, y, r)

→ only cares about feature differences correlated with r

Across many resamples:

correlated signal accumulates

uncorrelated noise cancels

The paper formalizes this with a minimum description length (MDL) framing: how many bits does the model need to absorb to represent what the training signal demands? Their hypothesis is that SFT demands absorbing “many bits” because it tries to match a full demonstration, while RL demands far fewer “useful bits” because the reward labels what matters.

A tour of the experiments (what they actually did)

The experimental setup is straightforward but carefully done. They evaluate on GSM8K for the “clean” story and then on a broader math suite (MATH, AIME, AMC, and others) using the evaluation sets popularized by SimpleRL. They train either with SFT (next-token prediction) or with RL (GRPO) using an exact-match reward.

They compare four approaches: full finetuning, classic LoRA, LoRA-XS, and TinyLoRA. For LoRA and variants they sweep ranks, and for TinyLoRA they also sweep how aggressively they share parameters across layers/modules. They sweep learning rates across update sizes because effective learning rate changes as the number of trained parameters changes.

Two plots are the center of gravity: (1) the RL sweep, which shows TinyLoRA bridging from 1 parameter up to LoRA-scale updates with a smooth curve; and (2) the SFT sweep, where the same tiny-update regime barely improves over baseline.

Diagram 3: The two curves you should remember

(Conceptual sketch; the paper has the real plots.)

GSM8K accuracy

^

| RL (GRPO)

| .-''''''''-.

| .-'' ''-.

| .-'' ''-.

| .-'' ''-.

| .-'' ''-.

|.' ''.

|

| SFT: much flatter in the tiny-adapter range

+-------------------------------------------------> trainable parameters (log scale)

1 10 1e2 1e4 1e6

A subtle but important detail: the paper notes that even at 10⁴ trained parameters, models see little degradation relative to full finetuning on GSM8K, which motivates asking “how low can we go?” That’s the justification for inventing TinyLoRA in the first place: once the curve is already strong at 10k parameters, exploring the next order of magnitude down is natural.

They also evaluate beyond GSM8K. One datapoint highlighted in the introduction: finetuning with just 196 parameters retains 87% of the absolute improvement across six difficult math benchmarks. That pushes the claim from “GSM8K quirk” to “a pattern across harder suites,” though still within math-style reasoning.

Ablations: what matters when you only have tens of parameters?

When your trainable state is tiny, hyperparameters stop being “tuning knobs” and start being “the whole model.” The paper runs ablations on smaller backbones to understand which TinyLoRA design choices drive performance.

The first ablation is the frozen SVD rank r. Intuitively, you might think keeping more singular directions should help, because it gives the update more expressivity. The paper finds diminishing returns: moving from r=1 to r=2 helps a bit, but larger ranks can hurt. Their hypothesis is that higher frozen rank introduces more degrees of freedom in the frozen basis, which makes it harder to optimize the tiny trainable vector v.

The second ablation is the tradeoff between u (the size of the trainable vector per module) and n_tie (how aggressively you share v across modules). This is the “capacity budgeting” problem of TinyLoRA. The paper’s guideline is practical: if you have a fixed budget, increase u as much as you can (down to u=1 per module) before increasing how much you tie across modules. In other words, local expressivity beats global sharing until you hit the floor.

Diagram 4: A TinyLoRA capacity budget

Total trained parameters ≈ (n layers) × (m modules/layer) × u / n_tie You can shrink updates by: - lowering u (less per-module expressivity) - increasing n_tie (more sharing across modules) Paper's practitioner heuristic: spend budget on u first only then increase sharing

This ablation is important because it clarifies what “13 parameters” really means. It’s not that one scalar is magically enough for the entire model in all cases. It’s that, for some tasks, there exists a surprisingly low intrinsic update dimension—and you can approach it by combining (1) a compact parameterization and (2) aggressive sharing.

Bit-constrained training: why fp32 can win

One of my favorite small observations: once you measure update size in bytes rather than parameters, weird things happen. In distributed training, communication is often the bottleneck, so bytes are what matter.

The paper studies “scaling in the bit-constrained regime,” where you might have tens or hundreds of parameters, but you care about total update size. It compares sharing strategies and numeric precision, and reports a surprising result: storing parameters in fp32 can be more performant “bit-for-bit” than bf16/fp16, even after accounting for fp32 being twice as large.

Why might that happen? The paper doesn’t overclaim, but it’s plausible that when you only have a handful of degrees of freedom, quantization noise and optimizer dynamics matter a lot. If your update vector is only, say, 64 numbers, then the difference between 16-bit and 32-bit representation could be the difference between “a stable steering dial” and “a noisy one.” If you ever do on-device adaptation with micro-adapters, this is a practical thing to test.

The engineering hack: testing new adapters without writing kernels

TinyLoRA is a new LoRA variant. In principle, serving and training frameworks need custom kernels to apply it efficiently. The authors ran RL inside VERL and used vLLM for inference—but vLLM’s LoRA support has constraints and doesn’t support LoRA variants.

Their workaround is elegant: do inference using merged model weights (so the adapter is “baked in”), and only use the true LoRA-form computation for the final forward pass needed for gradients. That creates a mismatch between what the sampler saw and what the gradient step assumes, so they mitigate it using truncated importance sampling.

This is a nice pattern to keep in your toolbox: if your inference engine can’t support a new adapter, but you can cheaply merge weights, you can still run RL-style loops without implementing kernels for every experimental idea. The mismatch correction is the price you pay, but it’s often cheaper than systems work when you’re still exploring.

So… what are the 13 parameters doing?

The paper is careful here, but it offers a plausible explanation: the “knowledge” for GSM8K may already be present in the base model, and the finetuning step may mostly change style—in particular, the tendency to generate longer outputs. The suggestion is that “learning to generate longer outputs” might be achievable in very few parameters, and longer generations can materially improve math reasoning.

That idea aligns with a lot of practitioner intuition: reasoning performance is extremely sensitive to behaviors like “don’t rush,” “show intermediate steps,” “check your answer,” and “use a consistent format.” These can look like “style,” but they also function as a compute allocation policy. In other words: you can get smarter by thinking longer, even if you didn’t become smarter in a deeper algorithmic sense.

If that’s right, then TinyLoRA is not a universal “learn any skill with 13 numbers” result. It’s a strong claim about a particular kind of post-training in a particular regime: large pretrained models + verifiable reward + tasks where more deliberate decoding unlocks latent competence.

The paper also notes backbone-specific quirks: Qwen-2.5 models appear much more responsive at small update sizes than LLaMA-3 in their experiments. That’s an important caveat if you try to reproduce: the “intrinsic update dimension” might depend on architecture details, pretraining, or instruction tuning.

Scaling trends: larger models need fewer control parameters

A broader theme the paper emphasizes is scaling: as model size increases, LoRA becomes more effective at smaller parameter counts. Put differently: if you hold dataset and objective fixed, larger backbones appear more “controllable” with fewer trained parameters.

This is not entirely shocking if you believe in an “intrinsic dimension” story: bigger models can represent more functions, and finetuning might mostly be selecting which of those functions you want. But it’s still striking to see the trend extended into the regime where the update is measured in bytes.

Scaling intuition: Goal: reach ~95% of peak performance on a task As backbone size ↑ minimal update size ↓ Why you should care: - personalization becomes cheaper - distributed training comms get easier - "behavior patches" become plausible artifacts

The practical implication: if you’re shipping many task variants, the adapter-storage and adapter-swap story changes dramatically. Smaller adapters mean you can store and serve more variants concurrently in memory, which matters for scalable personalization.

How I’d use this as a builder

If you’re thinking, “cool paper, but what do I do with it?”, here are a few concrete angles.

1) If you have a verifier, try micro-adapters + RL

This is the most direct takeaway. If your domain has an automated correctness check (unit tests for code, parsers for structured outputs, exact-match for math, constraint satisfaction), you can often run RLVR-style training. The paper suggests that in that setting, tiny parameterizations can be enough to get most of the gain. You don’t need TinyLoRA specifically to benefit from the “RL is information-dense” insight, but TinyLoRA gives you a tool to explore just how low the update dimension can go.

2) Treat adapter size as a systems knob, not a research constant

Many teams pick an adapter rank based on habit (“rank 8 is fine”) and never revisit it. This paper is a reminder that adapter size is not just a training detail—it affects memory footprint, comms cost, and how many variants you can serve. If you are building a product where each customer or workflow gets its own “behavior patch,” then a 100× reduction in adapter size is not an optimization; it’s a new product shape.

3) Use TinyLoRA as a probe for “steering vs learning”

You can also use this as an analysis tool. If you can improve a task with an adapter that is too small to memorize much, that’s evidence that your finetuning is amplifying capabilities already present in the base model. If you need a large adapter, maybe you’re injecting knowledge or new mappings. This is not a proof, but it’s a useful diagnostic.

4) Keep an eye on safety and governance

There’s an obvious governance implication: if “meaningful behavior changes” can be packaged into kilobytes, distributing, auditing, and controlling those changes becomes a different problem than auditing full model checkpoints. Micro-adapters could make it easier to deploy patches—but also easier to distribute undesirable behavior deltas. If this direction becomes mainstream, I expect we’ll need tooling that treats adapters as first-class artifacts with provenance, testing, and policy constraints.

Limitations (the paper is explicit about these)

The authors emphasize that their findings are limited to math datasets and math-style reasoning. The “tiny updates work well” story may or may not generalize to domains like science writing, open-ended planning, or creative tasks. Math is convenient because it’s verifiable and widely studied, but it’s not the whole world.

There’s also a subtle contamination question hovering in the background of all reasoning work: if the base model has already seen similar problems during pretraining, then “steering” into a better decoding strategy can look like “learning,” even if it’s mostly unlocking memorized patterns. The paper doesn’t claim to solve that; it simply notes that different model families behave differently at tiny update sizes, which is consistent with “what’s already inside matters.”

Finally, TinyLoRA is an extreme parameterization. If your goal is maximum performance, you may still want larger adapters or full finetuning. The point is not that you should always use 13 parameters; the point is that the frontier is far lower than we assumed, and RL seems to move that frontier in a principled way.

A closing thought

If you take the paper seriously, it suggests a reframing of “post-training for reasoning.” At least in math, we might be seeing something closer to programming a pretrained model than teaching it: the base model already has latent competence, and RL with a verifier supplies a clean signal that selects and amplifies that competence.

TinyLoRA is the extreme version of that: a tiny, information-dense patch that flips the model into a better mode. Whether or not 13 parameters is a stable number across domains, the direction is clear: as models scale, the “control bandwidth” you need to elicit a behavior can shrink dramatically.

Paper: “Learning to Reason in 13 Parameters” (Morris et al., 2026) • arXiv:2602.04118

Speak fuller prompts. Get better answers.

Stop losing nuance when you type prompts. Wispr Flow captures your spoken reasoning, removes filler, and formats it into a clear prompt that keeps examples, constraints, and tone intact. Drop that prompt into your AI tool and get fewer follow-up prompts and cleaner results. Works across your apps on Mac, Windows, and iPhone. Try Wispr Flow for AI to upgrade your inputs and save time.